Astronomers are uncovering new ways to study the universe’s first stars, objects too distant and faint to observe directly, by examining the ancient 21-centimeter radio signal left behind by hydrogen atoms shortly after the Big Bang. Understanding how the universe shifted from complete darkness to the first glow of starlight marks a major milestone in […]

Astronomers are uncovering new ways to study the universe’s first stars, objects too distant and faint to observe directly, by examining the ancient 21-centimeter radio signal left behind by hydrogen atoms shortly after the Big Bang. Understanding how the universe shifted from complete darkness to the first glow of starlight marks a major milestone in […]

Click the Source link for more details

A 13-Billion-Year-Old Signal Could Finally Reveal the First Stars

Scientists Uncover a New Pain Switch That Could Transform Treatment

Researchers found that neurons release an enzyme, VLK, that activates pain signaling from outside the cell—an unexpected mechanism. Removing VLK dulled pain in mice, while adding more heightened it, all without impairing normal movement. This suggests a safer way to treat pain without targeting risky receptors inside neurons. The discovery also provides new clues about […]

Researchers found that neurons release an enzyme, VLK, that activates pain signaling from outside the cell—an unexpected mechanism. Removing VLK dulled pain in mice, while adding more heightened it, all without impairing normal movement. This suggests a safer way to treat pain without targeting risky receptors inside neurons. The discovery also provides new clues about […]

Click the Source link for more details

Unexpected Findings: Cleveland’s Prehistoric Sea Monster Was Unlike Most Of Its Kin

Eddie Gonzales Jr. – AncientPages.com – Approximately 360 million years ago, during the Late Devonian Period, a formidable armored fish called Dunkleosteus terrelli dominated the shallow subtropical seas that once covered what is now Cleveland. This species belonged to the arthrodires, an extinct group of shark-like fishes characterized by bony armor protecting their head and torso.

Instead of traditional teeth, Dunkleosteus possessed sharp bone blades in its jaws, making it one of the largest and most fearsome predators of its time. Cleveland’s prehistoric sea monster had a mouth twice as large as that of a modern great white shark.

Dunkleosteus terrelli is recognized as Earth’s first vertebrate “superpredator,” thriving during the Age of Fishes, when North America was positioned near today’s Rio de Janeiro. Since its discovery in the 1860s, this prehistoric giant has fascinated both scientists and the public alike. Its distinctive skull and jaw structures are displayed in museums around the world. However, despite its popularity and iconic status among prehistoric animals, Dunkleosteus has received relatively little scientific attention over the past century.

Newly described muscle anatomy (right) and overall jaw anatomy of Dunkleosteus terrelli (center), compared to a more typical arthrodire (left). Credit: Russell Engelman/Case Western Reserve University

An international team of researchers, led by Case Western Reserve University, has recently published an in-depth study on Dunkleosteus that offers new insights into this ancient armored predator. Although Dunkleosteus is often seen as the quintessential representative of the arthrodire group, the study reveals that it differed significantly from most of its relatives and exhibited several unique characteristics.

“The last major work examining the jaw anatomy of Dunkleosteus in detail was published in 1932, when arthrodire anatomy was still poorly understood,” said Russell Engelman, a graduate student in biology at Case Western Reserve and lead author. “Most of the work at that time focused on just figuring out how the bones fit back together.”

Arthrodire fossils present unique challenges for paleontologists. Because these ancient fish had bodies primarily composed of cartilage, only their bony head and torso armor are commonly preserved in the fossil record. Additionally, their remains are often found crushed and flattened, which can complicate efforts to accurately study and reconstruct these prehistoric creatures.

“Since the 1930s, there have been significant advances in our understanding of arthrodire anatomy, particularly from well-preserved fossils from Australia,” Engelman said. “More recent studies have tried biomechanical modeling of Dunkleosteus, but no one has really gone back and looked at what the bones themselves say about muscle attachments and function.”

A team of researchers from Australia, Russia, the United Kingdom, and Cleveland has advanced the study of Dunkleosteus by examining specimens housed at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, which boasts the world’s largest and best-preserved collection of these fossils.

Dunkleosteus is believed to have existed globally during the Devonian period. However, unique environmental conditions in ancient Cleveland led to an exceptional preservation of skeletal remains in what is now a layer of black shale rock. This layer has been revealed over time through river erosion and road construction projects in the area.

The researchers’ detailed anatomical analysis revealed several unexpected findings:

- A cartilage-heavy skull: Nearly half of Dunkleosteus’ skull was composed of cartilage, including most major jaw connections and muscle attachment sites—far more than previously assumed.

- Shark-like jaw muscles: The team identified a large bony channel housing a facial jaw muscle similar to those in modern sharks and rays, providing some of the best evidence for this feature in ancient fishes.

- An evolutionary oddball: Despite being the poster child for arthrodires, Dunkleosteus was unusual among its relatives. Most arthrodires had actual teeth, which Dunkleosteus and its close relatives lost in favor of their iconic bone blades.

Rewriting arthrodire evolution

The study provides important evolutionary context for Dunkleosteus, revealing that its bone-blade specializations—and those of its relatives—were adaptations for hunting large fish. Notably, these features evolved independently in other arthrodire groups as well. The blade structures enabled these predators to bite sizable chunks from their prey, according to Engelman.

Graphical abstract showing the relative size of Dunkleosteus compared to a human figure—before and after the new calculations. Credit: Russell Engelman/Case Western Reserve University

These findings emphasize that arthrodires were not primitive or uniform animals; rather, they represented a highly diverse group of fishes that thrived in various ecological roles throughout their history. As Engelman notes, this research reshapes our understanding of both Dunkleosteus and the broader diversity within arthrodires, demonstrating that even well-known fossils can still provide valuable new insights.

Source: EurekAlert

Written by Eddie Gonzales Jr. – AncientPages.com – MessageToEagle.com Staff Writer

Click the Source link for more details

Scientists Overturn 20 Years of Textbook Biology With Stunning Discovery About Cell Division

Scientists have uncovered an unexpected function for a crucial protein involved in cell division. Reported in two consecutive publications, the finding challenges long-accepted models and standard descriptions found in biology textbooks. Researchers at the Ruđer Bošković Institute (RBI) in Zagreb, Croatia, have uncovered that the protein CENP-E, once thought to function as a motor pulling […]

Scientists have uncovered an unexpected function for a crucial protein involved in cell division. Reported in two consecutive publications, the finding challenges long-accepted models and standard descriptions found in biology textbooks. Researchers at the Ruđer Bošković Institute (RBI) in Zagreb, Croatia, have uncovered that the protein CENP-E, once thought to function as a motor pulling […]

Click the Source link for more details

Scientists Stunned as Moss Survives 9 Months in Open Space

Researchers discovered that moss spores can survive nearly a year exposed directly to space. Despite intense UV radiation and temperature swings, most spores remained viable when returned to Earth. Their protective casing acts as a natural shield, enabling resilience even scientists didn’t expect. The results open doors to using hardy plants for future off-world agriculture. […]

Researchers discovered that moss spores can survive nearly a year exposed directly to space. Despite intense UV radiation and temperature swings, most spores remained viable when returned to Earth. Their protective casing acts as a natural shield, enabling resilience even scientists didn’t expect. The results open doors to using hardy plants for future off-world agriculture. […]

Click the Source link for more details

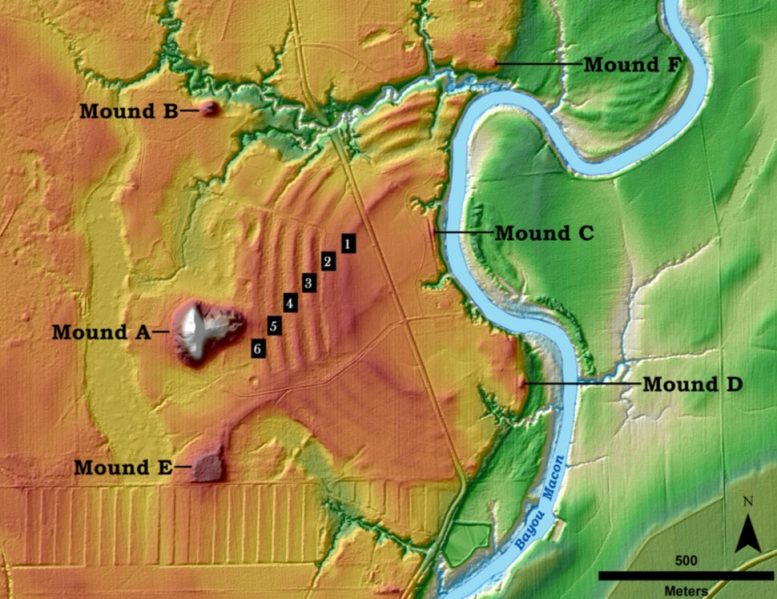

Archaeologists Uncover a New Purpose Behind One of North America’s Greatest Mysteries

New evidence suggests Poverty Point’s monumental mounds were created not by a ruling elite, but by egalitarian groups drawn together by shared ritual purpose. Some 3,500 years ago, hunter-gatherer groups began shaping enormous earthen mounds along the Mississippi River at Poverty Point, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in northeast Louisiana. “Conservatively, they moved 140,000 dump […]

New evidence suggests Poverty Point’s monumental mounds were created not by a ruling elite, but by egalitarian groups drawn together by shared ritual purpose. Some 3,500 years ago, hunter-gatherer groups began shaping enormous earthen mounds along the Mississippi River at Poverty Point, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in northeast Louisiana. “Conservatively, they moved 140,000 dump […]

Click the Source link for more details

Open Positions – Purdue Institute for Drug Discovery – Purdue University

Open Positions – Purdue Institute for Drug Discovery Purdue University

Click the Source link for more details

Enigmatic Stone Structure And Undeciphered Inscription Near Bulanık Village, Kars Province, Turkey – Still Unexplained

Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – The five-meter-tall and solitary stone structure atop a hill near Kars, Turkey, has long caught people’s attention. However, not for what is known about it, but rather for all that remains unknown. Overlooking Bulanik village, the summit—referred to by locals as “Ziyaret Tepesi” (“Visiting Hill” or “Pilgrimage Hill”) or “Evliya Tepesi” (“Saint’s Hill” or “Holy Man’s Hill”), respectively —is a fascinating landmark.

This unusual construction has origins that are shrouded in mystery. With no records to explain its purpose or history, this enigmatic site invites thoughtful speculation and raises intriguing questions about the stories that may lie hidden within its stones.

It is believed that the structure did not appear at this location by accident. Located about 26 kilometers from Kars, between Yahni Mountain and Dumanli Mountain, this soft-stone hill holds an ancient secret that has never been solved. No satisfactory explanation for its existence in this place has ever been given.

Its construction appears intentional, the result of careful planning rather than chance. Yet, there are no inscriptions to guide us, no similar buildings to compare it with, and no stories passed down through local memory. At present, the structure stands without any clear association to a specific date, culture, or name.

On the eastern slope of the structure, facing exactly towards the medieval ruins of Ani, there is a nearly two-meter-high inscription carved into a flat stone. However, its script remains a mystery, and the language it represents hinders identification.

The region’s residents believe the structure may belong to an ancient civilization. Yet there are no clear answers regarding it or the purpose of the inscription that was once carved. For now, the carving only remains as an enigmatic marker on a hill, waiting patiently for exploration and understanding.

The inscription is a puzzle. Image source.

Was it once a watchtower or perhaps a boundary marker? Another proposed explanation is that the stone structure could have served as a sacred site for ancient ritual ceremonies.

There was a time when the landmark represented a tempting target for treasure hunters. Now, this remarkable site in Turkey’s eastern highlands is protected by village guards. This action is really needed because for many years, the mysterious construction drew seekers of fortune, who conducted unauthorized digging in the area.

See also: More Archaeology News

The villagers believe that only an official archaeological project can truly preserve the site’s integrity and unlock its historical significance for future generations to cherish and learn from.

No doubt, the mysterious landmark of the region, which has long drawn the interest of residents, plays a significant role in Kars’s historical timeline.

Both the residents and researchers hope that it will be included in future studies of Kars’s broader archaeological landscape. With its direct line of sight to Ani and a distinctive inscription, this site may offer much more than just local intrigue; it could provide evidence of an undocumented phase in the region’s cultural history.

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Click the Source link for more details

The Problem with Britain’s Pensions

In May 2025 Keir Starmer, a prime minister with one of the largest majorities in history, backtracked on proposals to means-test the winter fuel allowance which has been paid to pensioners every year since 1997. There was a good case for the reform. Public finances are strained and, in the absence of rapid economic growth or tax hikes on working-age people, the government needed to make cuts somewhere. Surely some of the best-off people in society, when incomes are adjusted for housing costs, could accept the government did not need to contribute to their heating bills? Yet pensioners – almost 20 per cent of the population – as well as a majority of the general public, according to YouGov polling, would not. British politics seems incapable of confronting one of its biggest challenges. Such concerns are nothing new. Financing old age has been the most significant problem for the welfare state since its inception.

This much was clear in 1942. The economist William Beveridge, who had been commissioned to write a report that is now viewed as the blueprint for the modern welfare state, warned MPs that improving the existing state pension scheme, which provided pensions for men who had worked insured occupations and their wives after the age of 65, and for everyone over 70, was going to require some difficult choices. Beveridge recommended introducing a new universal pension scheme for over-65s, which would start at a low rate and increase gradually over the course of 20 years as workers built a surplus of contributions that would pay for their retirement. Jim Griffiths, Labour’s Minister of National Insurance, thought differently. ‘The men and women who had already retired had experienced a tough life’, he argued. ‘In their youth they had been caught by the 1914 war, in middle age they had experienced the indignities of the depression, and in 1940 had stood firm as a rock in the nation’s hour of trial. They … should not wait for twenty years.’ Full pensions were paid immediately but, given the cost implications, they were set below subsistence level.

Caught in a trap

A welfare state that included such a meagre benefit was a key feature of the decades after 1945. It was generally believed that poverty only existed in a small number of exceptional circumstances because the postwar social security system prevented it from being more widespread. Yet it was notable that politicians of all stripes were prepared to concede that pensioners were not among those who ‘had never had it so good’, as the Conservative prime minister Harold Macmillan put it in the late 1950s. The reason for pensioners’ difficulties was fairly clear. Britain was home to more old people, both relatively and absolutely, than ever before, with the proportion of men over the age of 65 and women over the age of 60 rising from 6.2 per cent to 13.5 per cent of the population during the first half of the century; 1.4 million more were expected to be claiming pensions by the end of the 1950s than when the scheme started a decade earlier. The Treasury wanted to keep costs down but the result satisfied nobody. An increasing number of pensioners were so poor that they had to go cap in hand to the National Assistance Board (NAB), the body that distributed means-tested benefits to people who fell between the cracks of the National Insurance scheme; two-thirds of the NAB’s more than 1.5 million claimants were pensioners by the late 1950s. But many also wondered if the state pension scheme was too expensive to sustain. Sir Thomas Phillips, whom the Conservatives appointed to chair the Committee on the Economic and Financial Problems of the Provision for Old Age in 1952, thought it was impossible to calculate a pension that was sufficient to live on and palatable to the Treasury. He argued that the retirement age should be put back up to 70 to bring down costs.

Politicians were trapped. Phillips’ recommendation would lead to electoral consequences no government wanted. But how to get more money into the system? An important part of Beveridge’s appeal was egalitarianism: everyone paid the same flat-rate contributions and was entitled to the same benefits. The consequence, however, was that everything was tethered to what the lowest paid workers could afford. Politicians therefore fell back on encouraging the growth of occupational pensions to compensate for the state system’s failures. Yet this would create, as Richard Titmuss, a pioneering social policy scholar, put it in the mid-1950s, ‘two nations in old age’: those with access to an occupational or private pension, who were able to live a comfortable life, and those reliant on the state pension, which everyone knew was insufficient.

Half pay

An influential group within Labour, now in opposition having lost power in 1951, thought their party’s fortunes, as well as the country’s, were dependent on modernisation of the welfare state. The likes of Richard Crossman, a member of the party’s ruling National Executive Committee who held a social services brief, drew on academics, many from the London School of Economics, to design radical new policies. In 1957 Labour announced ‘National Superannuation’: an earnings-related pension scheme that required contributions proportional to income and paid out benefits based on lifetime earnings. Subtle mechanisms of redistribution would make the poorest pensioners better off. Labour marketed the scheme as delivering ‘half pay on retirement’ and printed 52,000 copies of a pamphlet outlining it, which sold out within a year.

Nothing approaching this dream became a reality, though. One reason was the precedent that the policy might set. Few politicians had the stomach for a complete overhaul of social security on earnings related lines, which they thought would be called for if anything like National Superannuation were implemented. Of more importance, however, were the ideological leanings of the Conservative governments of the 1950s. Against any further expansion of the welfare state and concerned about the implications for the private pension industry, whose services they preferred, the Tories seized gleefully on a number of small errors in Labour’s calculations, such as including income raised from contributions from Northern Ireland but not pensions that would then be paid out there. Nevertheless, the electoral appeal of Labour’s proposals was obvious, leading the Tories to immediately announce their own earnings-related addition to the state pension, albeit one that was the palest of pale imitations, in which the value of extra entitlements failed to keep pace with inflation, illustrating that the intention was to raise more money, rather than improve benefits.

Labour certainly intended to address the worst elements of state provision for old age when Harold Wilson made it to Downing Street in 1964. But anything other than incremental improvements to existing benefits slipped down the agenda quickly. A very distant relative of National Superannuation, the State Earnings Related Pension Scheme was finally adopted in the late 1970s. The fact it was a heavily watered down version of proposals that had been around for 20 years only underlined that genuinely far-reaching reform was often out of reach for Labour and Conservatives alike.

Overhaul

There has never been one reason for the failure to pursue ambitious ideas in these areas; poor policy design, political expediency, and an inability to elevate goals other than cost-saving have all played their part. Perhaps the most important issue, though, is that problems have not remained static. If the five decades after the Second World War were dominated by a failure to meet pensioners’ needs, the next 20 years saw politicians fail to face up to the fact that significantly improving the generosity of state support for old age, without addressing the underlying mechanisms that paid for it, was consuming unsustainable levels of resources. The apex of this problem is the ‘triple lock’, which guarantees the state pension increases each year by the highest of inflation, average annual earnings, or 2 per cent. Pensioner poverty is still a serious problem, but when Gordon Brown, the Labour chancellor of the exchequer, introduced the winter fuel allowance in 1997, pensioners were the poorest demographic in Britain; 25 years later they are among the richest.

Does history contain any lessons for thinking about the trouble with reforming the welfare state or, indeed, implementing change elsewhere? The path dependency inherent in political decision making is clearly important. Although we are a long way from the 1940s, our current arrangements are a clear descendant of Beveridge’s plan, not least in many pensioners’ continuing reference to having ‘paid in’ during their working lives. In this respect, as Andrew Marr recently observed, the state pension is pretty much the only part of our social security system that maintains a link with the old contributory principle, meaning few politicians are prepared, or have the political capital required, to overhaul it.

We might also infer that certain conditions are required for substantial reform. Given that Beveridge’s major concern in 1942 was to enrol everyone in what were believed to be the best existing state schemes, the extent of change after the Second World War is often overstated. Yet the war did make some decisions much easier because, in the context of shared sacrifice, arguments about the importance of providing for everyone in old age were much more compelling than concerns about the cost implications of doing so. Even this observation has its limits, though. What dramatic change did the Covid-19 pandemic – an event as disruptive as war – produce? Perhaps the only hope for reformers is that it is still to come.

Chris Renwick is Professor of History at the University of York.

Click the Source link for more details