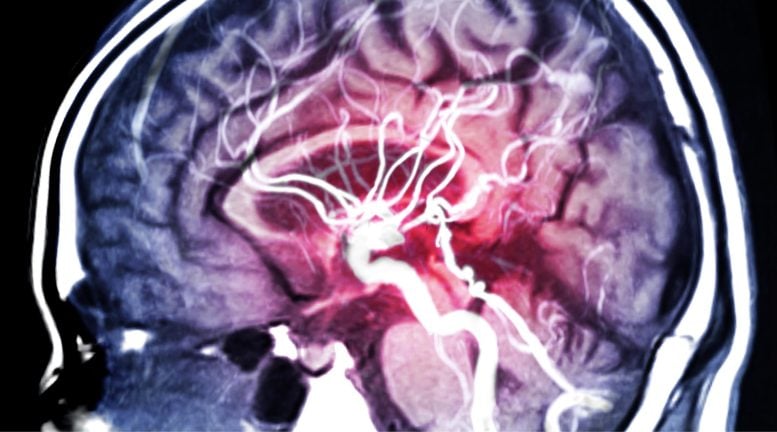

A new study shows that hypertension quietly disrupts brain cells and blood-vessel integrity well before blood pressure spikes. Hypertension can begin harming blood vessels, brain cells and white matter long before a rise in blood pressure is detected, according to a new preclinical investigation from researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine. These early effects may help […]

A new study shows that hypertension quietly disrupts brain cells and blood-vessel integrity well before blood pressure spikes. Hypertension can begin harming blood vessels, brain cells and white matter long before a rise in blood pressure is detected, according to a new preclinical investigation from researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine. These early effects may help […]

Click the Source link for more details

Hypertension Wreaks Havoc on the Brain Before Blood Pressure Ever Rises

Study Debunks Major Myth: AI’s Energy Usage Is Significantly Less Than Feared

Energy consumption in the U.S. is changing how people perceive the environmental risks associated with AI. New research challenges the common assumption that artificial intelligence places a heavy burden on the climate. The findings indicate that current levels of AI use have only a small impact on global greenhouse gas emissions and could even support […]

Energy consumption in the U.S. is changing how people perceive the environmental risks associated with AI. New research challenges the common assumption that artificial intelligence places a heavy burden on the climate. The findings indicate that current levels of AI use have only a small impact on global greenhouse gas emissions and could even support […]

Click the Source link for more details

AI Uncovers Hidden Traces of Life in 3.3 Billion-Year-Old Rocks

Scientists used advanced chemical analysis and machine learning to detect hidden molecular traces of life in rocks over 3.3 billion years old. The AI identified biological signatures with more than 90% accuracy and revealed early signs of photosynthesis far earlier than previously known. Discovery of Ancient Chemical Traces of Life A new investigation has identified […]

Scientists used advanced chemical analysis and machine learning to detect hidden molecular traces of life in rocks over 3.3 billion years old. The AI identified biological signatures with more than 90% accuracy and revealed early signs of photosynthesis far earlier than previously known. Discovery of Ancient Chemical Traces of Life A new investigation has identified […]

Click the Source link for more details

Historic Cargo Ship Mado 4 Loaded With Treasures Recovered From The Seabed Off Taean, South Korea

Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – The National Research Institute of Maritime Heritage (NRIMH) has announced the successful completion of a significant underwater archaeological project. South Korean archaeologists have retrieved the 600-year-old Joseon-era cargo vessel, Mado 4, from the seabed off Taean in South Chungcheong Province on Korea’s western coast. This operation is notable for marking the first full recovery of a vessel from this period, representing a significant milestone in maritime archaeology.

Mado 4 Recovered After 10 Years

Shipwreck Mado 4. Credit: National Research Institute of Maritime Heritage (NRIMH)

The recovery effort began in 2015 when Mado 4 was initially discovered. Over nearly a decade, experts conducted careful on-site conservation and analysis before raising the ship. Currently, Mado 4 is undergoing desalination and preservation processes in Taean to ensure its long-term stability.

This fully preserved 15th-century ship holds substantial historical significance. It offers valuable insights into the maritime infrastructure of the Joseon dynasty, which ruled Korea for over 500 years. The excavation of Mado 4 provides unprecedented physical evidence of the kingdom’s advanced sea-based tax collection and transportation systems during that era.

Green Pottery

The ship contained a significant collection of treasures. Among the discoveries were 87 celadon pieces, a distinctive greenish ceramic produced in royal workshops. Initial investigations at the wreck site uncovered over 120 valuable artifacts. These included high-quality porcelain intended for government tribute payments, crates packed with rice, and wooden tags indicating specific destinations for the cargo.

Green pottery was found on Mado 4. Credit: National Research Institute of Maritime Heritage (NRIMH)

Researchers, including specialists from South Korea’s Cultural Heritage Administration, have verified that the Mado 4 was an active part of the joun, a crucial state transportation network during its time. This system played a vital role in moving grain and official goods from regional storage sites to Hanyang (modern-day Seoul).

Dangerous Route

Evidence suggests that the vessel likely sank around 1420 while traveling from Naju, a significant grain collection center in South Jeolla Province. The route was known for its hazardous conditions—strong tides and rocky passages—which not only posed navigation risks but also contributed to the vessel’s exceptional preservation beneath layers of silt and sand.

Underwater archaeologists examined Mado 4. Credit: National Research Institute of Maritime Heritage (NRIMH)

The Mado 4’s structural features provide valuable insights into the era’s naval engineering practices. Unlike earlier Korean ships that typically had a single mast, this vessel employed two masts—a design believed to improve both speed and maneuverability.

Wooden pieces are inscribed with ‘Naju Gwangheungchang,’ indicating both the destination and the departure point of the ship. Credit: National Research Institute of Maritime Heritage (NRIMH)

Additionally, researchers identified repair work using iron nails on the ship, marking the first confirmed use of metallic fasteners in traditional Korean shipbuilding. Such findings shed light on technological advancements during the Joseon dynasty and offer new perspectives on maritime logistics during the period.

See also: More Archaeology News

Notably, investigators also found evidence of another sunken ship nearby. Preliminary analysis dates this second wreck to between 1150 and 1175 CE, potentially linking it to the Goryeo Dynasty period. If confirmed, it would predate Mado 4 by more than two centuries and become Korea’s oldest known shipwreck. Selected artifacts recovered from these sites are currently displayed at Taean Maritime Museum as part of “Ship of the Nation Sailing the Sea,” an exhibition open until February 2026.

Source: National Research Institute of Maritime Heritage (NRIMH)

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Click the Source link for more details

A Simple Daily Supplement May Help Ease Lingering Long COVID Symptoms

A new clinical trial explored whether raising cellular NAD⁺ levels with high-dose nicotinamide riboside could influence lingering neurological and physical symptoms in long-COVID. Millions of people around the world continue to live with persistent symptoms after a COVID-19 infection, a condition known as long COVID. These ongoing problems can affect people of all ages and […]

A new clinical trial explored whether raising cellular NAD⁺ levels with high-dose nicotinamide riboside could influence lingering neurological and physical symptoms in long-COVID. Millions of people around the world continue to live with persistent symptoms after a COVID-19 infection, a condition known as long COVID. These ongoing problems can affect people of all ages and […]

Click the Source link for more details

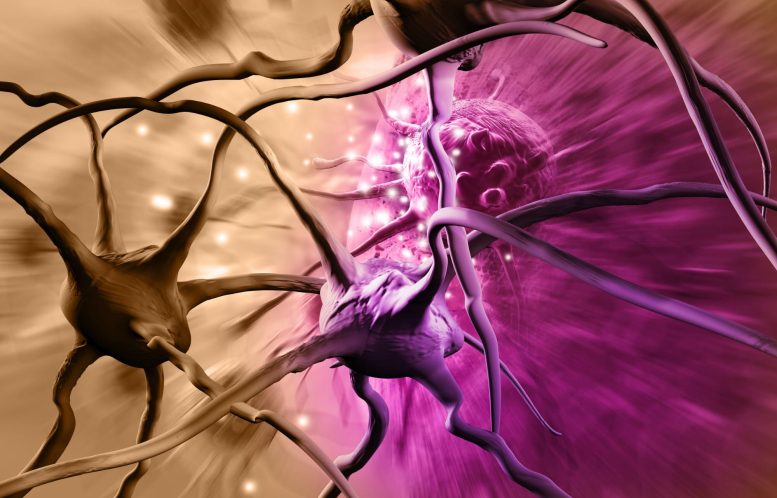

Stunning Results: Two Cheap Supplements Show Promise in Healing One of the Deadliest Brain Cancers

A new study indicates that glioblastoma becomes less aggressive after treatment with resveratrol and copper, a potentially game-changing finding that could pave the way for a radically new approach to cancer therapy. Treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy and immunotherapy are all designed with a single goal in mind: to destroy cancer. However, what if this […]

A new study indicates that glioblastoma becomes less aggressive after treatment with resveratrol and copper, a potentially game-changing finding that could pave the way for a radically new approach to cancer therapy. Treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy and immunotherapy are all designed with a single goal in mind: to destroy cancer. However, what if this […]

Click the Source link for more details

Roman Woman Depicted On Ancient Marble Sculpture Found In Crimea Identified

Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – An ancient Roman sculpted portrait of an unidentified woman was discovered in a residential house in the western section of Chersonesos Taurica, located in the southwestern region of the Crimean Peninsula, present-day Sevastopol, Ukraine. The woman’s identity remained a mystery—until now.

Identifying Roman portraits, especially those discovered in remote provinces or outside the Roman Empire, where written sources are scarce, poses a significant challenge. To overcome these difficulties, researchers use interdisciplinary methods to study ancient sculptures. These approaches help determine the age and origin of the material and can potentially link the artifact to a specific historical figure.

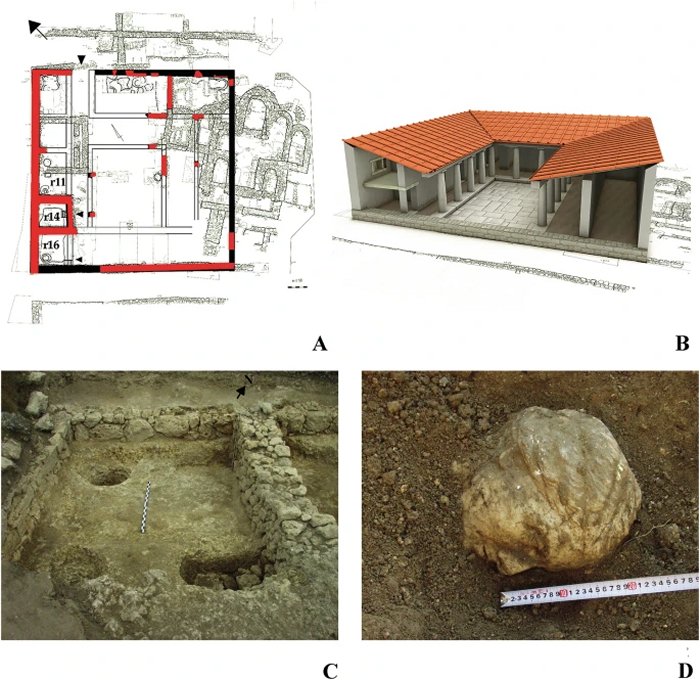

A The special plan of the residence in block LV (drawn by E. Klenina and P. Peresvetov). B The 3D reconstruction of the residence (created by M. Markgraf). C A semi-cellar of room No. 16. D The marble head at the stratigraphic level during the moment of uncovering, the view from the southeast (photograph by A. B. Biernacki).

A research team from Poland and Spain adopted a comprehensive strategy that combined historical and art historical analysis with spectral-isotopic and traceological techniques. This multifaceted approach enabled them to identify the individual commemorated by the sculpture found at Chersonesos Taurica.

The Dorian Greek city was established in 422/421 BC, replacing an earlier Greek settlement that dated back to the late sixth century BC. By the last quarter of the second century BC, Chersonesos had gained strategic importance for Rome, serving as a key transit point for moving Roman troops to Asia Minor. In recognition of its significance, Rome granted Chersonesos a special political status called eleutheria, making it a free Grecian city and an ally of the Roman Empire. Despite this autonomy, real authority rested with wealthy families closely connected to Rome. The actions of local officials led to an increase in political, economic, and military dependence on Rome—a relationship reflected in daily life and extending into cultural and spiritual spheres.

The earliest known description of Chersonesos’s ruins comes from Marcin Broniewski, who visited during a diplomatic mission in 1578. His account is one of the first detailed records about Crimea and the northern Black Sea coast in modern European history. Archaeological interest began much later; excavations began in 1827, focusing on uncovering early Christian relics.

Despite nearly two centuries of exploration at Chersonesos, research into portrait sculpture has been limited due to significant challenges such as extensive fragmentation and a lack of precise archaeological context for most finds. To date, only five fragments of marble portrait sculptures have been discovered at the site. Notably, one marble sculpture portrait was recently found exceptionally well-preserved—the first example from Chersonesos unearthed within a clearly defined archaeological context—marking an important milestone for further study in this field.

Laodice, The Wife Of Titus Flavius Parthenocles

A recent study by scientists from Poland and Spain has identified an ancient marble sculpture of a woman’s head as a portrait of Laodice, a Roman woman who lived during the first centuries CE. The researchers made this connection after examining the sculpture, which a Polish-Ukrainian archaeological expedition discovered in 2003 in the Chersonesos Taurica region (present-day Sevastopol, Crimea, Ukraine). They determined that the face likely depicts Laodice, who was married to Titus Flavius Parthenocles—a city council member and representative of one of Chersonesos’s most influential families.

Illustrations of the sculpture of the head of a woman (photographs by A.B. Biernacki).

Professor Elena Klenina from the Faculty of History at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan led the research team. She had long suspected that this marble head represented a person of high social status, based on its craftsmanship and the excavation site’s context. However, “a detailed, interdisciplinary analysis was needed to confirm this hypothesis,” she said. This new identification offers valuable insight into both local history and Roman-era portraiture.

The researchers conducted a comprehensive examination of the sculpture using several scientific and analytical techniques. These included spectral-isotopic analysis of the marble to determine its origin, wear testing to assess the sculptor’s skill level, carbon-14 dating, and materials science studies of the layers on the head’s surface. Additionally, a stylistic analysis was performed by an art historian from Spain, complemented by historical and epigraphic analyses to provide further context and understanding.

See also: More Archaeology News

“The use of interdisciplinary methods in research allowed us to not only determine the date and provenance of the material, but also link the sculpture to a specific historical figure,” Professor Klenina explained and added that in the first centuries CE, “Roman women played an active role in political life both within the Roman Empire and beyond its borders.”

The identification was made by scientists from Poznań, the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, and the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

The study was published in the journal Nature

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Click the Source link for more details

These Bumblebees Learned to Read “Dots” and “Dashes” Like Morse Code

A study shows that bumblebees can be trained to tell the difference between long and short light flashes. Researchers at Queen Mary University of London have discovered, for the first time, that an insect can choose where to search for food by evaluating how long a light cue lasts. The study focused on the bumblebee […]

A study shows that bumblebees can be trained to tell the difference between long and short light flashes. Researchers at Queen Mary University of London have discovered, for the first time, that an insect can choose where to search for food by evaluating how long a light cue lasts. The study focused on the bumblebee […]

Click the Source link for more details

‘The Maginot Line’ by Kevin Passmore review

Visitors to the Maginot Line fort at Schoenenbourg can experience something of the cold, dark, and damp conditions endured by the French forces who spent months living 30 metres underground during the Second World War. At the fort’s entrance, plaques honour the bravery of the combatants who were ‘handed over’ to the enemy on 1 July 1940 ‘without having been defeated’. The defiant tone of the memorials is in marked contrast with the criticisms that have often been levelled at the Maginot Line, and which lie at the heart of Kevin Passmore’s book.

The fall of France in 1940 remains shrouded in myth and controversy. Claims that the French lacked the will to fight, that soldiers sat idly behind outdated fortifications, and that the nation’s leaders were fundamentally defeatist continue to pervade popular perceptions. Passmore sets out to dismantle these myths. He disputes notions that the fortifications’ flaws reflected any cohesive national ‘mentality’, arguing instead that the problems were a result of political and military disagreements concerning pacifism or militarism during the period in which the defences were conceived and constructed. To make his case, Passmore adopts a more expansive approach than is suggested by the book’s title: the Maginot Line becomes a concrete lens through which to explore the history of France from the late 1920s to 1940.

It was not until five years after the death of André Maginot in 1932 that the forts and bunkers built along France’s eastern border became widely known by his name. Appointed as war minister in November 1929, Maginot argued that the defences would be essential for a safe reconciliation with Germany. Until 1929 French generals had considered a defensive war unlikely because Germany had been so weakened by the Treaty of Versailles. Nevertheless, while pacifism was widespread, most French people followed Maginot in wanting to ensure France’s ability to defend itself. It was not without some irony that the forts intended to protect national boundaries were built and staffed in significant part by immigrant workers, including from Germany and Italy, whose loyalties were often questioned by the French authorities. There were numerous cases of suspected espionage, although often they turned out to be unfounded. Big business competed for contracts and played a key role in the forts’ construction, which cost around six billion francs (roughly seven billion euros in today’s money). The designs were produced by a new generation of engineers educated at the École Polytechnique and reflected the modernist architectural styles of the time. The accommodation was compared to ‘upside-down versions’ of Le Corbusier’s skyscrapers and included central heating, air conditioning, and electric ovens long before they were common features of domestic homes. However, the sleeping areas provided little modern comfort. Damp was a significant problem, while air quality was poor.

As international tensions rose in the late 1930s, the issue of fortification became increasingly polarised. Those in favour of appeasement saw fortifications as a defence; others, especially on the left, were keen to directly confront fascism. After Belgium declared neutrality in 1936, a contrast emerged between the French government’s public support for a continuous barrier along France’s borders and the resources it allocated, as prime minister Édouard Daladier began to realise the significant financial cost involved. The government sometimes gave misleading messages about the inviolable nature of the fortifications to an anxious public. Propaganda films sought to reassure the people that the Maginot Line would protect France’s borders, while also emphasising that the fortifications were just one element in the defence plans.

At the outbreak of war in September 1939 the Maginot Line fulfilled its function of covering French mobilisation. However, the soldiers, who were not properly kitted out, endured the coldest winter since 1838. Many suffered from fatigue as a result of spending extended periods underground, though Passmore refutes suggestions that morale was poor during the Phoney War, and argues that it had improved significantly by the time the fighting began in May 1940. Far from seeing French military doctrine as the product of sclerotic thinking, Passmore points to commander-in-chief General Maurice Gamelin’s orders to advance into the Low Countries under the Dyle-Breda plan to emphasise how the French army did not merely seek refuge in defensive strategies.

The German army’s original intention of invasion through Belgium, sweeping northwards to the coast, would not have been so immediately disastrous for French forces. However, on 12-13 May 1940, German forces concentrated armoured and air forces on the weakest points in the French defences at Dinant and Sedan. Weaknesses in the depth of the northern fortifications meant that if one line fell, the others would be vulnerable to rear attacks. On 14 June 1940 six German divisions attacked the line from Saint-Avold to Puttelange with intense artillery bombardment followed by an infantry assault, compelling French forces to retreat. Ultimately, however, it was Allied weakness in the air, the inability to locate German forces, and communication problems that proved fatal to the French.

Overall, the Maginot Line’s contribution to the defence of France was mixed, Passmore argues. It blocked the easiest routes to Paris, Alsace, and Nice and was not the disproportionate burden on spending that it is often thought of as being. It was less susceptible to technological obsolescence than other forms of weaponry, though its construction coincided with a revived emphasis on mobility in battle. But most importantly, the book refutes the portrayal of the Maginot Line as a symbol of a defeatist French mentality that, having been originally propagated by supporters of Charles de Gaulle, has been echoed in numerous studies since 1945.

-

The Maginot Line: A New History

Kevin Passmore

Yale University Press, 512pp, £30

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Karine Varley is Senior Lecturer in French and History at the University of Strathclyde.

Click the Source link for more details

The Secret Fossil Fuel Network Running Through America’s Backyards

Millions of Americans live surprisingly close to fossil fuel infrastructure—not just oil wells and power plants, but also refineries, storage sites, and pipelines that make up a vast, mostly hidden energy network. A new nationwide analysis shows that 46.6 million people reside within about a mile of at least one such facility. Many of these […]

Millions of Americans live surprisingly close to fossil fuel infrastructure—not just oil wells and power plants, but also refineries, storage sites, and pipelines that make up a vast, mostly hidden energy network. A new nationwide analysis shows that 46.6 million people reside within about a mile of at least one such facility. Many of these […]

Click the Source link for more details